It was as if artist Gwendolyn Bennett was reaching out to me from the beyond. I had seen a landscape painting by the artist more than a week ago at the Swann Auction Galleries' twice-yearly sale of African American art.

The painting had the look and feel of the works of some older African American artists in the auction – men from the late 19th century whose subject of choice was the untouched beauty of nature. Bennett's work was called "Untitled (River Landscape)," an 8×12 oil on canvas signed G.B.J. with the year 1931. I made note of the price paid for the painting – $3,600 against Swann's estimated appraisal of $6,000-$9,000. (Click on photo below for a larger image.)

Gwendolyn Bennett's "Untitled (River Landscape)," 1931.

I didn't think any more about it until I got an e-newletter from my alma mater Paine College in Augusta, GA, about an assistant professor who had located one of Bennett's paintings. It wasn't just any painting: it was the oil that had been sold at Swann. I perked up because this was an amazing coincidence, and I wanted to know more about the discovery.

The professor was Belinda Wheeler, a native of Australia now living in the United States, who had written her dissertation on the artist and was working on a book about Bennett's life and works. She came across the painting on an auction site, negotiated a price for it, and hung it in her apartment in Augusta and a home in the Midwest, and in her office at the college.

"I loved looking at it and I didn't want to let it out of my sight," she said in an email interview.

Belinda Wheeler with the 1931 painting by Gwendolyn Bennett. Wheeler is writing a book on the artist.

When I began researching Bennett on my own, I realized that I knew her name. A friend of mine had come across Bennett's poem "To A Dark Girl" that he wanted tohave inscribed on his motorcycle.

It was a lovely poem, and it was among the works that made Gwendolyn Bennett a significant player among Harlem's literati in the 1920s. She was a Renaissance woman in the true sense of the word: poet, painter, illustrator, short-story writer, arts reviewer, teacher, columnist.

She had set out to be a painter, earning an art degree from Pratt Institute in New York in 1924 and spending a year studying art in Paris before returning to Harlem. She and her friend Regina Anderson, a librarian, were said to be among the people to suggest a dinner for Harlem writers that became the impetus for the Harlem Renaissance.

Gwendolyn Bennett with a still life that may have been lost. Credit: Modern American Poetry website.

Bennett was young – in her 20s – and those years were said to represent her most productive output of prose, poetry, paintings and drawings. She became better known, though, for her prose and poetry. In 1927, renowned writer Countee Cullen included "To A Dark Girl" in the anthology "Caroling Dusk." Most of her artwork from that time was destroyed in two house fires, according to Wheeler.

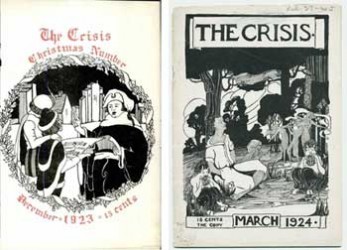

Her writings and drawings appeared in the NAACP's The Crisis and the Urban League's Opportunity magazines, among others. She also created cover illustrations for both of them, including a December 1923 drawing for The Crisis and the publication of her poem "Heritage" in Opportunity the same year.

In 1926, she and several other noted writers founded a literary journal called "Fire" to support the work of young African American artists, and she wrote a literary column called "The Ebony Flute" for Opportunity, which she edited for about seven years. One of her short stories, "Wedding Day," first appeared in "Fire." Bennett and her second husband retired to Kutztown, PA, in the late 1960s and opened an antiques shop.

Bennett was obviously a formidable presence during the Harlem Renaissance, so how did she get lost? That's one of the questions I put to Wheeler when I asked her to tell me more about Bennett and the painting that she found. Here are her answers. (Photo below is from the anthology "A History of African-American Artists" by Romare Bearden & Harry Henderson.)

Gwendolyn Bennett (center) with artists Norman Lewis (right) and Frederick Perry (left rear), and an unidentified woman during a WPA Artists Union protest of cuts.

Question:

How did you learn about Bennett?

Answer:

While I was a doctoral student at Southern Illinois University, I came across an article by scholar Jayne Marek about female editors and the Harlem Renaissance, and she included a list of African American female editors, which included Bennett. Marek's article did not go on to say anything else about Bennett, but when I saw Bennett's name I asked myself "Who is this woman and why don't I know anything about her?" This led me on a search of discovery. I soon found some of Bennett's poems and I learned more about her editorial role at Opportunity. She was a key figure in the development of the Harlem Renaissance as well as the time period immediately after the Renaissance, but there is still very little that has been written about her.

Question:

How did you find the Gwendolyn Bennett painting? What's the story behind the find?

Answer:

In February 2012, I located a picture on an auction site that reported to be selling a painting by Bennett. I was flabbergasted when I saw the painting because although Bennett was a noted painter, there is no known painting by her in existence today. Although I was excited about the potential find, I spent weeks talking with the owner who was selling the item to validate the painting. I liked the location of the painting (Florida) and the 1931 date (Bennett lived in Eustis, FL, during this time period), her signature (she was married to Dr. (Albert) Jackson at the time and she had added his last name to hers).

My hunch that the painting was Bennett's remained with me, but it was clear that if I purchased the painting I was going to be taking a risk and that I would have to spend a lot more time validating the painting's artist. The seller realized the risk I was taking and we negotiated a price for the painting and shipping. After I purchased the painting, I worked even harder to verify the painting:

a) verified the G.B.J. signature (I located various documents where Bennett signed her name G.B.B. or G.B.J.);

b) verified the signature and date with a black light to make sure that both inscriptions were produced at the same time;

c) verified Bennett's residency in Eustis, FL, at the time the painting was created (1931) through letter and diary entries located in archives;

d) further verified the signature and date with Bennett's closest living relative (I have this verification in a signed letter from Bennett's relative);

e) verified that the partial sticker on the back of the painting was from a former Washington, D.C., art supply store (Bennett lived in Washington prior to moving to Eustis, FL, so it is highly plausible that she brought art supplies from Washington with her); and

f) verified the type of painting – oil painting – Bennett reportedly used various types of paints including oil.

Gwendolyn Bennett was better known for her poetry and prose rather than her artwork.

Question:

Tell me about your decision to sell the artwork.

Answer:

I really went back and forth for at least six months deciding whether I would keep the artwork or not. I really love the piece, but it seemed inappropriate for me to keep it all to myself. In the end I felt that Bennett's painting must be shared with more people than my immediate circle. I did contact some museums and organizations about whether they would be interested in having the piece (as a donation) but Bennett's virtually unknown status in the artistic world generated little interest. I was worried about whether I would be able to keep Bennett's painting in a perfect climate to preserve it adequately, so I eventually decided that it should be passed on to someone who has the money and resources to take care of it properly.

Another reason I decided to sell the painting is that I believe there is more of Bennett's artwork out there, but people may not know what they actually own. (Bennett signed her name in various ways throughout her lifetime.)

Question:

How will you use the money?

Answer:

One, I will use part of the money generated from the sale to offset my expenses locating more of her artwork in the future. Two, I will be create some small book scholarships for some Paine College students to help offset their textbook expenses at the beginning of the semester.

Question:

Bennett appeared to be more a writer than a painter? Did she do many paintings?

Answer:

Bennett's writing is certainly more widely available to us, but she also created a lot of artwork during her lifetime. She created, for example, five magazines covers for Opportunity and Crisis, one of her line drawings is in an archive in Louisiana, and she painted a lot – letters, diary entries, photos. Conversations with her relatives validate this – we just don't have the concrete evidence (with the exception of this painting) to show just how much of an active artist she was.

Two Gwendolyn Bennettt cover illustrations from The Crisis magazine. Credit: Pratt Institute, left; Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, right.

Question:

Bennett seemed to be a major literary figure during the Harlem Renaissance. How did she get lost in history?

Answer:

Bennett was a significant figure in Harlem between 1924 and 1928 – publishing over 20 poems, 5 magazine covers, her column "The Ebony Flute," etc., but her first marriage and relocation to Florida significantly reduced her active contribution. When she returned to NY in approximately 1932, America was in the grip of the Depression and everything had changed. Bennett had a significant contribution after she returned, but unfortunately, most scholars ended their discussion of Bennett at 1928, thus largely contributing to her overlooked status today. (Let us not forget the power of recovery efforts, though. One of Bennett's good friends, Zora Neale Hurston, was also "lost" in history until Alice Walker highlighted her significant contribution.)

Question:

Tell me about the two books you're working on about Bennett?

Answer:

My first Bennett book recovers her complete history and it critically analyzes her literary and artistic contributions throughout her lifetime. The second book will be a collection of all her published and unpublished poetry.

Question:

Tell me a little about yourself.

Answer:

I am originally from Queensland, Australia. I have been in America for approximately 12 years. I completed my BA, MA and PhD here in America and after I completed my PhD I joined the Paine College faculty. I am in my second year as an assistant professor of English. At Paine I teach courses in American literature, African American literature, literary theory, Shakespeare, introduction to literature and composition. Next semester, I will be teaching a new course I designed on Australian literature and culture, which will devote a significant amount of class time to Australia's indigenous population.

My hobbies are searching archives and other places for lost treasures. For example, three and a half years ago I was at the Emory University archives and I was researching an unprocessed collection of a relatively unknown person who had a connection with some key figures from the Harlem Renaissance. Within about an hour of looking in the collection I found a typed manuscript of one of Langston Hughes' poetry collections which Hughes had signed and dedicated. Emory was thrilled with the discovery, as was I.

Related posts:

- Motorcycles and art

- James Van Der Zee's photos of Harlem

- African American painting? I think not

No comments:

Post a Comment